The MSU CVM DVM-PhD program admitted its first student in 2008 and currently has nine enrolled students. It is uniquely designed for the college’s 2+2 DVM curriculum, which includes two years of clinical rotations. Students are able to start and finish the DVM curriculum with their classmates, and a gradual phase-in of PhD training allows them to complete the PhD in a shorter amount of time following completion of their DVM.

The program prepares students who are committed to conducting research as an important aspect of their veterinary career, including both clinician scientists and traditional research scientists.

Graduates are on faculty at Rutgers University, Tufts University, Vanderbilt University, University of Central Florida, and Texas A&M University. Others are employed as veterinary medical officers at the U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, or USDA APHIS, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, and the Texas Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory.

Current standout students in the program include Cassie Barber, James Valentine, and Keegan Jones.

“Cassie has served as student program leader for a couple of years. She is a natural leader, and I am greatly appreciative of her assistance and the extra time she has devoted to helping address students’ needs,” Dr. Mark Lawrence, DVM-PhD program director, said. “James is very enthusiastic about parasitology research and has such a positive attitude. He is always encouraging other students, and his enjoyment of research is contagious.”

“And Keegan is taking the extra load of completing a population medicine residency at the same time as a PhD. He is a great student with an outstanding work ethic,” Lawrence continued.

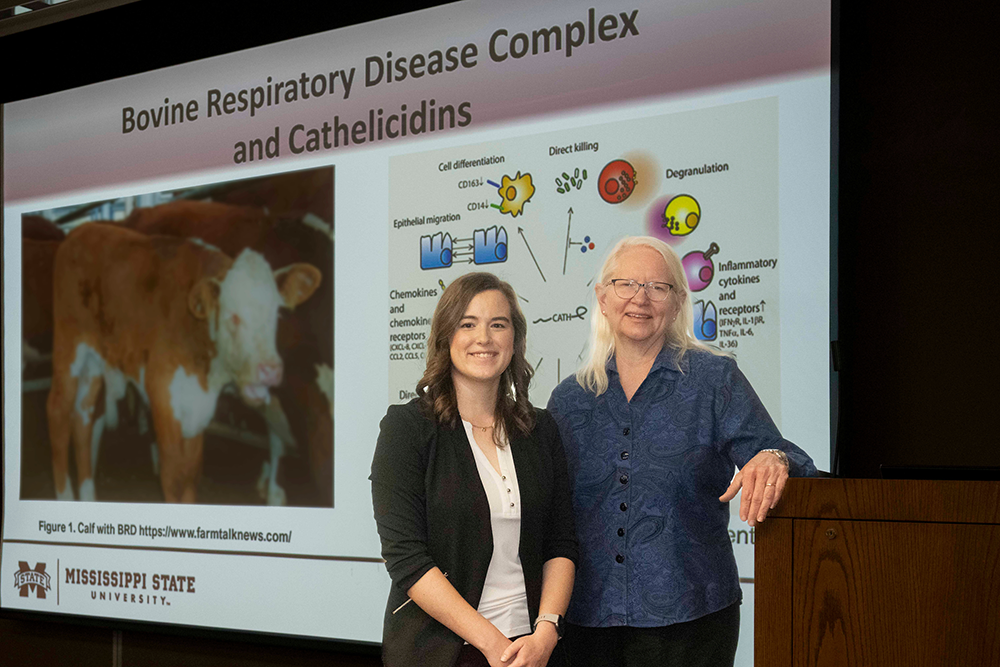

Dr. Cassie Barber

Aspiring Research Anatomical Pathologist

For Cassie Barber, veterinary medicine and research go hand in hand. Barber is preparing for a future as a research anatomical pathologist, an ambitious path that not only requires earning a DVM and completing a PhD but also pursuing a residency to become a Diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Pathologists.

“Choosing to pursue both degrees simultaneously was driven by financial considerations and my interest in my lab research,” Barber, who earned her DVM in 2023, said. “I genuinely enjoy the work my lab is doing, which made the combined degree path a natural fit.”

Barber has found the balance between her two programs, both manageable and rewarding, thanks to strong mentorship and faculty support. “My major professor has been incredibly supportive,” she said. “During vet school, I focused on becoming a well-rounded veterinarian, gaining experience in diverse settings such as exotic animal clinics, the CDC’s lab animal program, and all the clinical rotations offered. Then, during academic breaks, I got a head start on my research through literature reviews, writing proposals, and initiating projects.”

Barber’s PhD work focuses on molecular pathology, aimed at the natural progression of disease. Specifically, her lab is investigating bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV), which has a human counterpart, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), a major cause of illness in infants and the elderly. “By understanding why calves become ill, we may be able to develop a preventative strategy for this virus in both animals and humans,” she explained.

Barber’s clinical training and research experience complement one another in powerful ways: “My background in immunology, anatomy, physiology, and endocrinology gives me a unique perspective that someone without veterinary training might not have,” she said. “Clinical training helps me stay grounded, allowing me to focus not only on the small experimental details but also on the broader implications of the work.”

Looking ahead, Barber hopes to use her dual degrees, along with a pathology residency, to pursue research in animal health or drug development. “My ultimate goal is to contribute meaningfully to the advancement of medicine,” she noted.

James Valentine

Aspiring Researcher in Parasitic Diseases

James Valentine has always been fascinated by the hidden world of parasites and the stories they tell about animal and environmental health. He first explored those interests through a bachelor’s degree in biological sciences and a master’s in entomology, focusing on insect ecology and systematics. When he discovered MSU CVM’s combined DVM-PhD program, it felt like the perfect next step, a way to merge his love for animals with his passion for research.

Now in his fourth year of the program, Valentine balances DVM clinical rotations with doctoral work that takes him deep into the life cycle of parasitic trematodes found in alligators. His research blends fieldwork and genomics, using both molecular and morphological tools to clarify evolutionary relationships for Mississippi’s aquaculture industry, wildlife conservation, and the broader One Health approach to animal and public health.

“I’ve always been drawn to both animals and research, but it wasn’t until I started working on mosquito-borne disease ecology as an undergrad that I realized how much I enjoyed the investigative side of biology,” he says. “Pursuing a DVM-PhD felt like the most natural way to bridge clinical knowledge with ecological and molecular research, allowing me to approach parasitic disease with both a research and a clinical lens.”

That dual perspective has shaped Valentine’s veterinary training. He often draws on his background in parasite systems during clinical cases, spotting patterns and organisms that others might miss. He has even sequenced material from real-time cases to confirm diagnoses; this is evidence of how seamlessly his research informs his clinical work.

Balancing two demanding degrees isn’t easy, but the program’s flexibility and Valentine’s determination make it possible. He spends winter and summer breaks and multiple research electives advancing his PhD while sharpening clinical skills year-round. “Shifting between research and clinical thinking keeps me sharp and gives me a broader perspective,” he says.

Valentine plans to continue exploring the intersection of veterinary parasitology, molecular diagnostics, and disease ecology, whether in academia, government, or industry. His goal is to lead the research on host-ectoparasite interactions and emerging diseases, developing diagnostics that protect both animals and public health.

Dr. Keegan Jones

Aspiring Animal Population Health Researcher

Keegan Jones always wanted to be a veterinarian. “Fixing broken animals was what I knew as a ‘good job’ growing up; it was fulling, meaningful work that made a difference,” he said. But during his undergraduate years, he discovered a new passion: research. “I had always had this nagging curiosity to ‘know how we know’ facts,” he explained. “As it turns out, research is how we build that knowledge.”

That curiosity led to an important realization late in his junior year. “I had this career crisis. Did I really want to be a veterinarian if I could contribute to animal population health through research?” Jones questioned. “I started looking into graduate degree options. Lucky for me, Mississippi State offered the option to pursue a DVM and PhD concurrently under the guidance of several veterinary epidemiologists.”

Balancing the demands of two rigorous programs has proven challenging but rewarding. “Working on my PhD while completing my DVM involved primarily coursework. Since earning my DVM, I’ve started a residency concurrent with my PhD program, so there’s always something to do,” Jones said. “I’m grateful that my programs complement each other; my residency provides skills for my graduate work, and vice versa.”

Jones’s research focuses on developing a proxy test using vectors to detect bovine anaplasmosis, a disease often managed with long-term antimicrobial use. “As a veterinarian, I have a duty to my patients and a duty to preserve access to effective antimicrobials,” he said. “And an economical, less labor-intensive diagnostic test for anaplasmosis may help veterinarians make evidence-based decisions for the herds under their care.”

Jones’s clinical training and research intersect seamlessly. “The clinical training I use most is my training in epidemiology,” he noted. The same reasoning we ask veterinary students to apply to diagnostic tests translates well into research on diagnostic test development. Good diagnostic tests should help you decide whether an animal is sick.”

By blending clinical medicine and scientific discovery, Jones reflects the college’s commitment to advancing animal and public health through innovation and service.